I enjoyed "Arms of Nemesis" so much I immediately elevated Steven Saylor to the top of my favorite authors list and thereafter searched diligently for more of his work. Over the years I managed to "read" all of his books detailing Gordianus' sleuthing activities in the late Roman Republic, or at least thought I had until I noticed the publication date of "The Triumph of Caesar". I had confused it with "The Judgment of Caesar" so thought I had already read it until I took the time to read a synopsis of the plot and realized it was the most recent release in the series that had escaped me.

Like Gordianus, I, too, have grown gray over the years and identified with his desire in this latest episode to finally retire and simply enjoy reading in the quiet of his peristyle garden. But, the rich and famous are still jockeying for positions of power as the Roman Republic crumbles around them and no one is safe, even the mighty Caesar, who has finally emerged victorious from the Civil War with Pompey the Great and the optimates, placed Cleopatra on the throne of Egypt after defeating her brother and his generals and quelled an uprising in the east led by the King of Pontus.

As Caesar prepares to celebrate an unprecedented four triumphs, his wife Calpurnia has been told by her Etruscan haruspex (soothsayer) that there is yet another plot afoot to kill her husband. So, she summons Gordianus to discover the latest villain before the assassin can succeed and throw the Republic back into bloody turmoil.

Little is known about Calpurnia other than the fact that she was the daughter of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, a wealthy patrician who is thought to have owned the sprawling complex of the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum. Saylor portrays her as a politically savvy woman at the center of a huge web of spies who keep her informed about anything that could threaten her husband and thereby her position as the First Lady of Rome. If we look at the political machinations of her father, this portrayal seems to be quite probable rather than the image of a modest Roman matron painted by what few sketchy references we have in the ancient sources.

In 58 BC, when the consul, he [Piso] and his colleague, Aulus Gabinius, entered into a compact with Publius Clodius, with the object of getting Marcus Tullius Cicero out of the way. Piso's reward was the province of Macedonia, which he administered from 57 BC to the beginning of 55 BC, when he was recalled. Piso's recall was perhaps in consequence of the violent attack made upon him by Cicero in the Senate in his speech, De provinciis consularibus.The maxim "fiat justitia, ruat coelum" ("Let justice be done, though the heavens fall") is attributed to Piso.

On his return, Piso addressed the Senate in his defence, and Cicero replied with the coarse and exaggerated invective known as In Pisonem. Piso issued a pamphlet by way of rejoinder, and there the matter ended. Cicero may have been afraid to bring the father-in-law of Julius Caesar to trial. At the outbreak of the civil war, Piso offered his services as mediator. However, when Caesar marched upon Rome, he left the city by way of protest. Piso did not openly declare for Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus but remained neutral and did not forfeit the respect of Caesar.

After the murder of Caesar, Piso insisted on the provisions of Caesar's will being strictly carried out and, for a time, he opposed Marcus Antonius. Subsequently, he became one of Anthony's supporters and is mentioned as taking part in an embassy to Antony's camp at Mutina with the object of bringing about a reconciliation with Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. - NationMaster

Piso clearly engaged in power brokering at the highest levels and his daughter would surely have learned many valuable lessons about politics growing up in his household.

We also know from the ancient sources that Calpurnia believed in prophetic dreams so it would not be surprising if Calpurnia clandestinely relied on the services of an Etruscan haruspex.

Although haruspicy was considered by the Romans so important at one time, that the senate decreed that a certain number of young Etruscans, belonging to the principal families in the state, should always be instructed in it, by the late Republic the art had fallen into disrepute.

In de Divinatione, "Cicero (de Div. II.24) relates a saying of Cato, that he wondered that one haruspex did not laugh when he saw another." - Haruspices by William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.:But Calpurnia was not about to reject any tool at her disposal. Furthermore, the Pisones are thought to have had Etruscan origins themselves. Scholars think this explains their military service in Etruria during the Hannibalic War and consequent introduction into Roman political life.

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875.

|

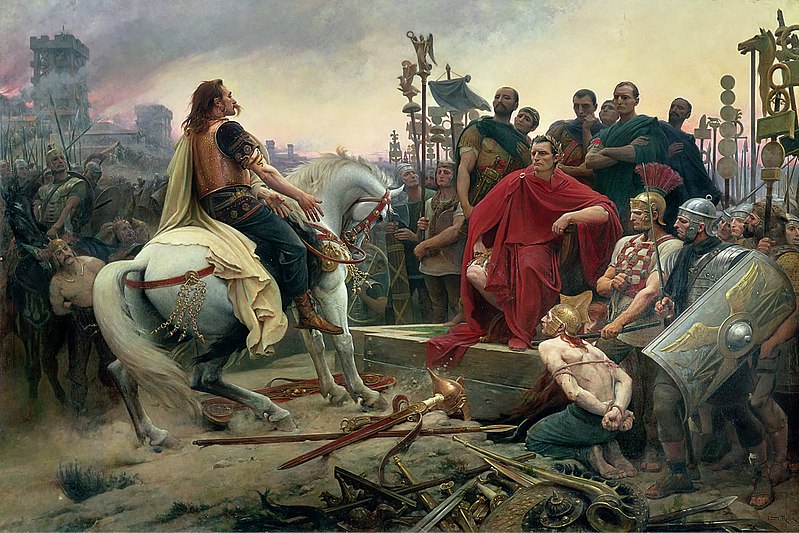

| Vercingetorix Throws Down his Arms at the Feet of Julius Caesar (1899) by Lionel-Noël Royer |

Although Gordianus does not want to become enmeshed in any more political intrigue, he is convinced to take on the case because he learns that Calpurnia had previously hired his old friend from Massilia, Hieronymous, who now lays dead from a single knife thrust to the chest in Caesar's study. So, for the sake of his friend, Gordianus accepts the commission.

As Gordianus retraces his friend's steps, we get the opportunity to meet more people whose names crop up in the history of the period. One of Gordianus' first appointments is to meet with Vercingetorix. Whenever I read about Vercingetorix, I can't help but envision the noble warrior with flowing hair and mustach depicted in one of my favorite paintings, Vercingetorix Throws Down his Arms at the Feet of Julius Caesar (1899) by Lionel-Noël Royer. But Gordianus finds a wretched man with matted hair, sunken cheeks and hollow eyes cowering in the depths of the notorious Tullianum, the prison that may have derived its name from the archaic Latin tullius "a jet of water" because the prison, constructed around 640-616 BC, by Ancus Marcius, was originally created as a cistern for a spring in the floor of the structure's lower level. (the prison consisted of two levels - the second of which contained prisoners lowered there through the floor of the upper room). Eventually a passage between the cistern drain and the Cloaca Maxima was constructed, to not only carry away the waste from prisoners but their bodies as well after their ritual strangulation.

|

| Drain the Cloaca Maxima in the Tullianum, renamed Mamertine Prison in medieval times |

I have actually visited the chamber that modern Romans think served as the Tullianum and peered into the hole opening into the Cloaca Maxima. I shudder to think what it would have been like to languish in that dank cavity awaiting execution.

Goridanus also visits the "House of the Beaks", the former home of Pompey the Great adorned with the ramming beaks of pirate ships captured in Pompey's campaigns. There, he finds an embittered Antony sodden with wine and consoling himself with a female actress. Antony is smarting from a public reprimand by Caesar for mismanaging Rome in Caesar's absence and has been placed on notice that Caesar expects him to auction Pompey's house and possessions since they were apparently not formally awarded to Antony for his services during the Civil War. Pouting like a child, Antony refuses to participate in the upcoming triumphs, despite his own significant contribution to the victory at Alesia, and petulantly plans to hold a rummage sale of Pompey's old mismatched cast offs to give the appearance of complying with Caesar's auction order. I think this passage really nailed the impetuous personality of Antony and his almost child-like contrariness. It was definitely a sharp contrast with Cleopatra's calculated worldliness.

Gordianus also mused about the possibility that Cleopatra herself may be plotting against Caesar. She certainly could have thought there was a possibility to wrest Egypt away from Roman domination if Caesar's death triggered yet another civil war. Caesar and Cleopatra were obviously at odds over Caesar's refusal to acknowledge Caesarion as his son although Caesar himself did not seem to have made his mind up yet about what role Cleopatra would play in the future. Like Gordianus, I too find it odd that he installed her statue in his new Temple of Venus.

Gordianus also interviews Cleopatra's sister, Arsinoe. Knowing her eventual fate at the hands of Antony's assassins in the sanctuary of Artemis in Ephesus, I couldn't help but find her a tragic figure. I have been particularly curious about Arsinoe after reading about the possibility that her remains may have been found in an Egyptian style tomb shaped like the Pharos lighthouse in Ephesus. Although the age of the young woman found in the tomb seems a little too young to me (15 - 18 years of age), I still think the possibility that the skeleton could be Arsinoe is exciting. (See my original blogpost about the discovery).

I also felt sorry for Arsinoe's tutor, the eunuch, Ganymedes. In this book he is portrayed as a somewhat effeminate creature although Ganymedes quite ably commanded Egyptian forces against Caesar after the death of the Egyptian general Achillas. It was Ganymedes who engineered the pollution of Caesar's water supply when Caesar and his troops were surrounded in Alexandria. Ganymedes marshalled the Egyptian navy to attack Caesar's fleet too. Although Ganymedes' seamen lost the naval engagement, he fought Caesar's forces to a standstill in a subsequent bombardment. But the Egyptian populace, like the Roman mob, were a fickle lot and eventually turned against Arsinoe and Ganymedes claiming they were tired of fighting under the leadership of a woman and her tyrant Ganymedes. Ganymedes fate is not described in Caesar's Alexandrian Wars. He simply disappears from the narrative after Caesar releases Ptolemy XIII who then took control of the Egyptian forces and was subsequently defeated by Caesar and drowned in the Nile. It is unlikely Ganymedes survived the return of Ptolemy even though Arsinoe, still a teenager, was surrendered alive to Caesar. But, it is such circumstances that invite the novelist's imagination so in this story Ganymedes is pitifully paraded in Saylor's version of Caesar's triumph .

I particularly enjoyed Saylor's descriptions of each triumph and the crowd interactions with the triumphator, Caesar. I could easily envision the mob shouting in unison like unruly sports fans as they sought to implore Caesar to "Spare The Princess" and "Kill the Eunuch!"

Despite all of these high profile suspects, though, Gordianus discovers that Caesar's conquests may actually not be the ultimate motivation for murder. The Roman Empire was built on centuries-old traditions and family pride was often tightly interwoven with ancestral contributions to historical tradition. Caesar's seemingly benign attempt to correct the Roman calendar appears to have ruffled important feathers too, including some of his own in-laws.

In the late Republic, the Roman calendar was based on a mish mash of solar and lunar calculations ordained by the second king of Rome, a Sabine statesman named Numa Pompilius.

"In Romulus' time, the calendar had been fixed at 360 days to the year, but the number of days in a month varied from twenty or less to thirty-five or more. Numa estimated the solar year at 365 days and the lunar year at 354 days. He doubled the difference of eleven days and instituted a leap month of 22 days to come between February and March (which was originally the first month). Numa put January as the first month, and may indeed have added the months of January and February to the calendar." - Biography of Numa Pompilius the Second King of Rome, About.com

Unfortunately, in the 700 or so years since King Numa's calendar had replaced the original calendar, even the leap month could not prevent the calendar from slipping out of sync with the actual seasons. Harvest festivals based on the calendar were being held before the harvest was even gathered. So Caesar sought to correct the calendar once and for all with the help of Egyptian astronomers. But, the Calpurnii Pisones prided themselves on their descent from King Numa - so much so that their revered ancestor, the Roman annalist L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi who was consul in 133 BCE, censor in 120 BCE and author of the Annales Maximi, is credited with more citations about King Numa in his writings than any other Roman historiographer.1

So Caesar's tampering with the calendar could be viewed as almost sacriligious by members of his wife's family. Furthermore, Caesar's opponents, always on the lookout for something to use against him, were sowing unrest by claiming the involvement of Egyptian astronomers made it look like his new Egyptian subjects were superior to average Romans.

Gordianus eventually manages to thwart those that would put an end to Caesar prematurely but we all know destiny cannot be permanently denied. Caesar would still find his at the end of dagger (or possibly 23 daggers) in the Theater of Pompey on the Ides of March in 44 BCE. I have yet to discover if Gordianus will be called upon to head that investigation!

Footnote 1: Gary Forsythe, The Historian L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi and the Roman Annalistic Tradition. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1994. Pp. xi + 552. ISBN 0-8191-9742-4.