But, just as in life, Verpa's death sends terror through his household as troopers of the city prefect round up the household slaves and herd them into a small windowless chamber where they will await the foregone conclusion of the official investigation before being executed in a most hideous manner in the arena.

After all, Roman law was clear. If any slave should murder his master, all slaves, considered complicit because the murder was not prevented, are deemed equally guilty.

But, this time, the outcome was not going to be as predetermined as in cases in Rome's past. The city prefect has appointed Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, temporary vice-prefect, to investigate, and the thriving young lawyer, known to history as Pliny the Younger, will not be content to simply go through the motions.

As the case begins to unravel, we find Pliny snared in not only a complicated murder investigation but an assassination plot woven about the imperial throne as well.

|

| Mosaic of a Charioteer at the Palazzo Massimo Photographed by Mary Harrsch |

Although I was only slightly familiar with the historical Pliny the Younger from my study of Pompeii and the Vesuvian disaster that claimed his uncle, Pliny the Elder, I found Pliny to be an interesting man in his own right and plan to read more of his letters as time permits. From what I found in my research, Dr. MacBain's portrayal of Pliny closely follows his real persona as discovered in the study of his own writings, the Epistulae (Letters), a series of personal missives directed to his friends and associates that were published in Pliny's own lifetime.

|

| Pliny the Younger's descriptions of the eruption of Vesuvius have been invaluable to modern volcanologists From the Discovery Channel's ''Pompeii'', courtesy of Crew Creative, Ltd |

"We know more about Pliny as a person than we do about most figures from antiquity," MacBain obeserves, "because he was a great letter writer. Through his letters we see many facets of the man. He was a Roman senator and a lawyer with a successful, if not brilliant, career in the imperial administration. He was a landowner with a beautiful villa on the Italian coast. He was a literary dilettante. He was rather vain, rather fussy. At the same time, conscientious and honest. He was curious about the natural—and supernatural—world. He was a very social animal, he had hundreds of friends. His most endearing qualities are his love for his young wife, Calpurnia; his generosity—he endowed a scholarship fund for the boys and girls of his home town; and his humanity towards his slaves and freedmen in an age when that was not common."

Calpurnia was actually Pliny's third wife. Childbirth was a hazardous undertaking in the 1st century CE and Pliny had already been widowed by it earlier in his life. So, we can certainly understand his worry over his young wife's advanced pregnancy as the story progresses.

MacBain also introduces us to the flamboyant poet Martial. This hairsute Spaniard is a pungent blend of crude comedy mixed with sudden, unexpected flashes of introspection. Although he was known for his ribald epigrams he could also pen verses that encouraged reflection on what was really important in life.

|

| Bronze applique depicting two togate men. Roman 50 - 75 CE. Photographed at the Getty Villa by Mary Harrsch |

"This is that toga much celebrated in my little books, that toga so well known and loved by my readers. It was a present from Parthenius; a memorable present to his poet long ago; in it, while it was new, while it shone brilliantly with glistening wool, and while it was worthy the name of its giver, I walked proudly conspicuous as a Roman knight. Now it is grown old, and is scarce worth the acceptance of shivering poverty; and you may well call it snowy. What does not time in the course of years destroy? this toga is no longer Parthenius's; it is mine." - Martial, On a Toga Given Him by Parthenius, Book IX, XLIX.

We meet Parthenius, a portly and scheming chamberlain of Domitian who acted as gatekeeper to the emperor as the story progresses and learn that even he has joined the inner circle of conspirators plotting Domitian's death. The chambelain was probably the recipient of many gestures offered to secure a position in the imperial court and someone who an aspiring poet would have had to flatter with verse if he sought to have a copy of his work reach the eyes of the emperor. Parthenius may have reciprocated with the gift of a toga that could have been worn by the poet to disguise his rather common upbringing and tout his court favor. But life takes a toll on togas as well as men and Martial confides at the end of the passage that now the toga is more worn and threadbare, it is much more suitable for the real man it now covers.

Martial actually was a friend of Pliny the Younger, who, like many young aristocrats, dabbled in poetry himself and enjoyed socializing with literary celebrities. I appreciate the inclusion of this aspect of Pliny's nature in MacBain's portrayal of Pliny and the opportunity to gain insight into the life of one of Rome's celebrated grammarians living on the precarious edge of imperial patronage.

Image by mharrsch via Flickr Image by mharrsch via Flickr |

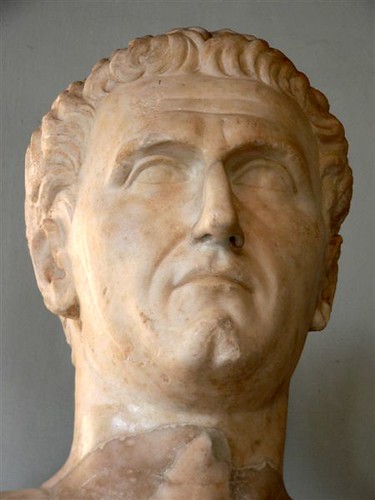

| Bust of Domitian 1st century CE |

Of course, we also get to meet one of Rome's most sinister emperors, Domitian. Our first encounter occurs when Pliny is invited to a strange dinner party where the guests are first ushered deep into the bowels of the palace and a bizarre charade takes place where an encounter with Hades himself is reenacted without the guests being forewarned, in an effort to elicit damning confessions from them. This scene is very reminiscent of a similar audience with Domitian described by Steven Saylor in his novel "Empire".

Domitian's pleasure derived from tormenting Rome's social elite is chilling. I know Professor Tuck related that he felt many of Domitian's more "transgressive" activities reflected the emperor's efforts to redefine Roman virtus but I can't help but assign a proclivity to sadism to Domitian's psychological profile.

At one point in the novel, Pliny watches as Domitian squashes flies in a prelude to a petulant diatribe against first, Pliny, then Roman society as a whole. As Domitian veers wildly from condemnation to bestowing favor upon his hapless visitors and demanding kisses, we can easily understand the fear that must have permeated Domitian's inner circle. We also gain sympathy for Domitian's wife, one of the co-conpirators, who is described as bruised so severely even heavy makeup cannot conceal her condition.

|

| The emperor Nerva photographed at the Capitoline Museum by Mary Harrsch |

Nerva was Domitian's immediate successor and he is portrayed in the book much as he was thought to have been in life - a reluctant Caesar who other conspirators selected mainly because of his age, with the thought that he could be a placeholder for a short time until someone more suitable could be found. But there was more to Nerva than the conspirators may have realized. If we examine another passage from Martial, we see that the poet, experienced in assessing the motivations of others, lends insight into this "man who would be king":

"He who ventures to send verses to the eloquent Nerva, will present common perfumes to Cosmus, violets and privet to the inhabitant of Paestum, and Corsican honey to the bees of Hybla. Yet there is some attraction in even a humble muse; the cheap olive is relished even when costly daintiest are on the table. Be not surprised, however, that, conscious of the mediocrity of her poet, my Muse fears your judgment. Nero himself is said to have dreaded your criticism, when, in his youth, he read to you his sportive effusions." - Martial, To Nerva, Book IX, XXVI.Martial, at least, has more than just a little trepidation about Nerva's accession and, as the novel concludes, Pliny soon discovers himself that the new emperor has an edge of ruthlessness about him that Pliny will be unable to deflect.

So we leave Pliny, sobered by his new reality, and must say goodbye to Martial as he leaves for his childhood home in Hispania. Although Pliny has more adventures ahead of him, Martial will no longer share them and, historically, dies within a few years of his return to Spain.

I look forward to Pliny's next adventure as we fast forward ten years and Pliny embarks on a new career as governor of the province of Bithynia-Pontus in Asia Minor. I see that his new side-kick will be that salacious gossip-monger Suetonius so I'm sure that will make for a wild ride!